On the rooftop of a Danchi apartment building, the ghost of a demon-possessed giant koi haunts a too-small pond. It asks the last detective in town, Lady Love Dies, for evidence of the things people did when they lived there. What games they played to pass the time, what songs they listened to. What mementos from the past shaped their present, before their predetermined future destroyed them.

When Lady Love Dies satisfies the ghost demon-koi’s curiosity, it starts to move on to the afterlife. She stops it. Doesn’t it want to wait until she’s solved the Crime to End All Crimes?

Credit: Kaizen Game Works

Credit: Kaizen Game Works

How much do you really care? is a question I’ve been asking Love Dies, and myself, too.

Danchi’s architect, the Architect of Paradise, is an immortal cultist named Carmelina Silence. Silence designed the Danchi apartments to house some of the thousands of humans that the Syndicate cult—Love Dies’ people—kidnaps, enslaves, and sacrifices to their alien gods.

Apparently, the Danchi apartments were so inimical to human existence that, after several surface-level attempts to improve quality of life (like installing koi ponds), Silence condemned the apartments and built detached homes. The kidnapping, enslaving, and sacrificing continued.

In finding my way around Paradise, I came to understand two things:

1) Carmelina Silence isn’t a good architect, and

2) It probably wasn’t just the apartments that were responsible for people’s suffering.

Paradise Killer is a murder mystery video game by Kaizen Game Works. On the eve of the rebirth of Paradise, the Syndicate’s ruling council is brutally murdered. The immortal investigator Lady Love Dies is brought out of exile and charged with solving the crime.

The problem: the pocket-dimension paradise was mostly empty at the time of the murders. Most of the immortal Syndicate had already moved to Perfect 25, the next island in the chain, the final iteration of Paradise. Most of the mortal population, on the other hand, had been ritually slaughtered. The murderer is still on the island, but it’s possible the mastermind is out of reach.

Obelisks and crystal statues of alien gods are littered everywhere, the vending machine mascots are sentient, the ghosts are getting philosophical. A virus-headed demon nicknamed Shinji keeps popping up and shooting the shit with me, the skeleton bartender’s covering his tracks while serving up whisky blends called Night Alone and Vortex. I’m hacking the Nightmare Computer with hieroglyphs. Paradise Killer leaves little cosmic-ness to the imagination, and it’s a wild world to have to find my footing in before I can even begin to contemplate means and motivation.

Credit: newgamenetwork.com, Kaizen Game Works

(I found this essay by Recusant helpful in parsing the Myst-meets-vaporwave of it all.)

Lady Love Dies, returned from exile, needs to make sense of what’s changed: the Syndicate in-fighting, the hidden allegiances to various eldritch gods, medical minutiae of demonic possession, the infinite crimes against humanity. Then there’s the shadow hanging over her head—her own previous crime, in which she was seduced by a god named Damned Harmony and nearly ended Paradise herself.

In an interview between Ivy Taylor and Kaizen Game Works’ Phil Crabtree , Taylor notes that “[w]hen it comes to narrative design, weirdness without reason is a sin”.

In the early days of the Cosmic Mystery Club, I would have set Paradise Killer aside. I wanted to focus on mysteries in which the sleuth’s understanding of their world cracked open at the touch of the cosmic. I wanted to reckon with the existential shift that comes with that brush against the unknown, that sliver of insufficient understanding.

But Lady was born and raised in the upper echelons of a cosmic horror cult. On the spectrum of Nope’s “What’s a bad miracle?” to The Good Place’s Time Knife, Lady Love Dies is firmly in Time Knife Territory.

Credit: screenrant.com, NBC

Navigation in this debut game is kind of awful, so I lost my way countless times. As I kept looping around the empty island, talking to the remaining people, searching for clues, I started to get kind of blasé about the whole city-pop-and-crystalline-skulls vibe too. Of course these people would have a corporate office lobby-themed cemetery. Ugh, who designed this blood-spattered sacrifice chamber?

But this jaded feeling is on purpose, I think, too. Realizing that some parts of the island were receding into the background helped me understand Love Dies’ blind spots, and how those might steer her moral compass.

Lady Love Dies was born into Paradise, but she spent the last three million days in exile. Is it enough to see Paradise’s architectures of justice with new eyes?

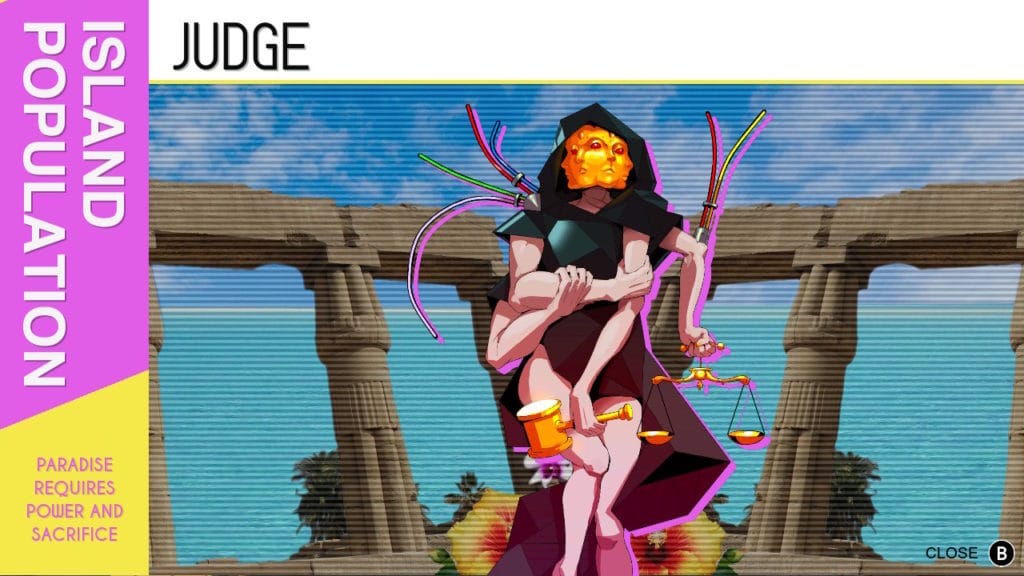

Paradise Killer purposely sets you the task of solving one crime while inundating you with evidence of countless others. The Syndicate’s arbiter of Justice, the Judge, brought in Love Dies because the primary suspect of the council murders, a mortal human named Henry Division, is just too obviously a sacrificial scapegoat.

Credit: gamespace.com

The game doesn’t hide that Paradise is fueled by a whole capitalism-tinged human sacrifice scheme. So from about five minutes in, I was extremely okay with the fact that the Syndicate council was dead.

The player is allowed to choose how Love Dies responds to certain questions about this society. You can criticize the Syndicate, and sometimes it will bring out other people’s misgivings and regrets, but sometimes that just makes their ultimate loyalty to the Syndicate more clear. It all had a realistic ‘what will you actually do about it’ feeling: I wasn’t making choices that determined how Love Dies would act. I was just saying stuff.

As I got closer to these sometimes charming, sometimes horrible people, I found myself sorting them into piles of less- and more- guilty of crimes bigger than the council murders. Who furthered which abuses against the sacrificial mortal underclass? Who enabled those who exploited their power? Who told themselves they were doing it for good reasons?

And as I started to become numb to Paradise’s charms, I considered the differences between Love Dies and myself. She might come back to Paradise society with a critical eye, but it’s not my critical eye. Even when the crime challenges her assumptions, her conclusions might not sync with my conclusions. Thus the ultra-concentrated cosmic environs: Love Dies is a little bit blind to the horrors obvious to me, but also provides insight I can’t.

Spoilers:

Everyone’s involved in the council murders. But not everyone’s equally involved in Paradise’s greater crimes. Some suspects, if allowed to walk free, would take advantage of the power vacuum to further those crimes. Some would leave Paradise altogether if they could. And you know what? Some of these people are just dicks.

Paradise Killer is a mystery about ‘who is justice for’?

I spent hours and hours wandering around the island, marveling, ignoring, scorning it. I found evidence to support accusations against anyone and everyone. And the Judge, provided I gave good courtroom theater, was jazzed to accept whatever I chose to share, ignore whatever I withheld. I had options:

1. Play it straight. Solve the council murders. Root out the conspiracy.

2. Accuse everyone I believed guilty of greater crimes, in the hopes of making the future a shred better.

And a bonus option, offered by the Judge:

3. Take my gun and kill anyone I wanted afterward, regardless of the trial.

Among the conspirators is the architect of Paradise, Carmelina Silence. (What would Paradise look like without her? How would my attention to the aesthetics of Paradise change?)

Love Dies and the Judge are both pillars of the Syndicate’s architecture of justice. The case stirs up a lot of old, bad blood, and I couldn’t help but think of how similar cases might have been handled in the past. (Especially given that third option, the gun option.) In giving the player these options, Paradise Killer demonstrates how judicial systems so often work to serve purposes aside from innocence and guilt. But you can do all that with a story set in a county courthouse in Arizona. What does Paradise bring to the table? Why make this a cosmic mystery?

Alongside the best speculative fiction, this game places people—its characters, but also you, the player—into extremely unrelatable circumstances and considers what those people might do. Even under these eldritch conditions, nobody was out here making the same unfathomable choices that their alien gods might make. I understood everyone’s motives. Each character is a meditation on people’s limits under conditions of fantastical inequality, victims or beneficiaries.

Do I play these weird mystery games for the thrill of the solve? To soak up the vibes? (To work through my Shin Megami Tensei demons?) I might not live on an island with gods in the stars and obelisks scattered on the sand, but Paradise Killer reminded me to pay attention to when I let myself see the world around me, and when I let myself ignore it.

(I didn’t fire the gun once after the trial was over. I went to speak with the scapegoat one last time and turned the game off. Forget it, Lady, it’s Paradise. Nobody gets what they want.)

MINUTE MYSTERIES

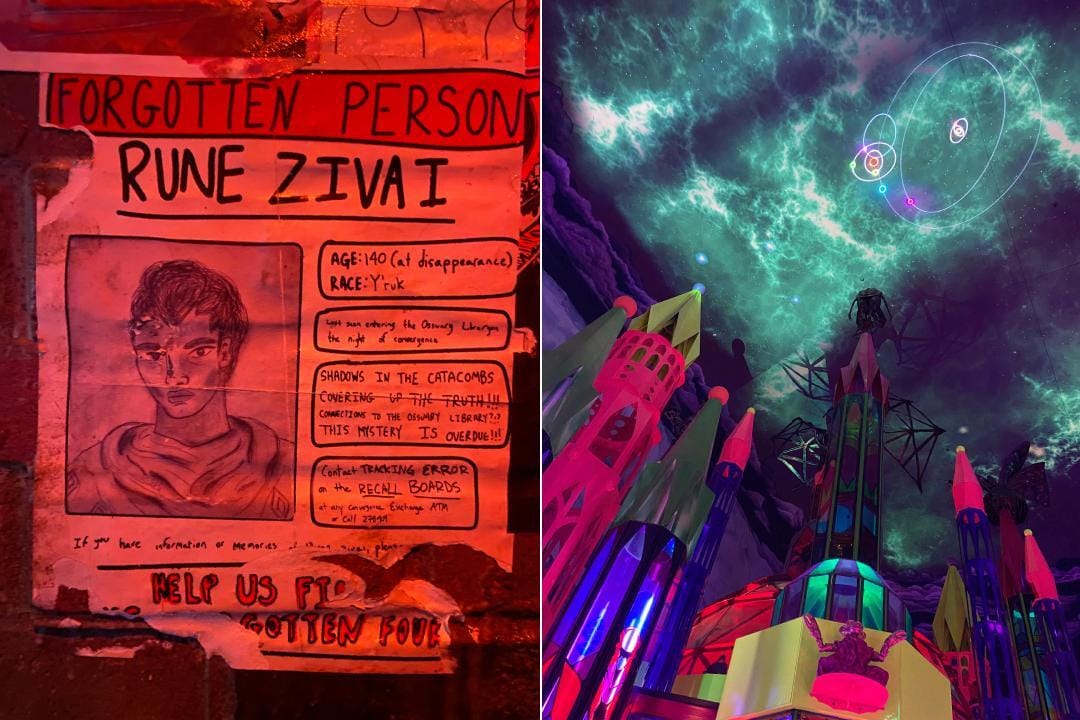

Speaking of ultra-concentrated cosmic vibes, I recently visited Meow Wolf’s Convergence Station art installation in Denver during a three-day museum blitz. Of all their narratives, this is Meow Wolf at its most sci-fantasy epic, but there’s still a mystery at its heart. I was familiar with most of the installation’s memory-fueled story from a deep dive into the art and business practices of Meow Wolf a couple of years ago. This allowed me to take my time, appreciate the details of the craft and storytelling on display, connect the dots without needing to first figure out what the dots were. Unfortunately that signature Meow Wolf maximalism burned me out before I was done. But, appropriately for Convergence Station, I’m happy to now have my own memories to fall back on, rather than secondhand evidence of the memories of others.

⏳︎

Credit: msn.com, Netflix

Like pretty much everyone, I’m charmed by Wake Up Dead Man, the latest Knives Out film. Each installment sets gentleman sleuth Benoit Blanc’s cynicism against his desire to support goodness in others, and Wake Up Dead Man is keen to challenge him. This movie gives ample time to both impulses, reflecting off suspect Father Jud’s conflicting instincts for self-preservation and helping those in need. The mystery itself is at times precariously fiddly—a good match for a lightly cosmic mystery about the intersection of belief and truth and the power religious leaders have to perpetuate hardship or provide refuge.